Vocabulary and Validation

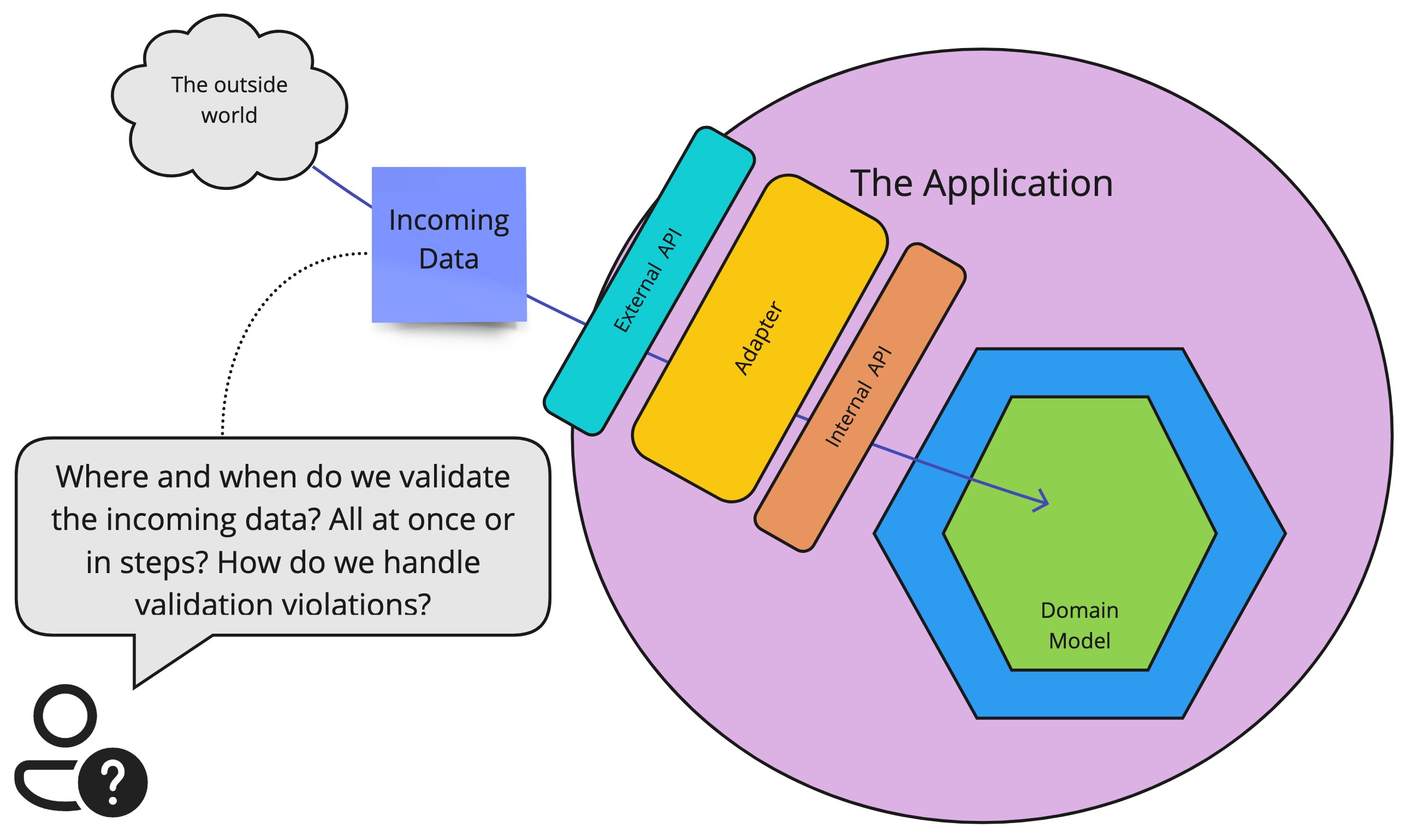

A discussion that I keep encountering over the years is the following: How and where to handle the validation of your incoming data requests?

- Do you validate this data inside your domain model? Or outside your domain model? After all, it is kinda business logic. But do we want the raw data to pollute our domain?

- We also don’t want to have the same logic in different places. Since it is then only a matter of time before it gets out of sync and different logic is applied depending on which entry path we take into our application.

- What to do if it isn’t valid data? Throw exceptions? Return once we encounter the first data error? Thus forcing the client to correct the data entry one by one?

In this blog post, I’ll try to convey my approach to the topic, hoping that it has some value for someone.

The problem

For clarification purposes, we will use a simple example. A request/command that is received contains a name, a shoe size, and an amount. These simple data fields each have their restrictions.

- The name must be at least 2 characters and a maximum of 100. With no whitespace at the front or the end.

- The shoe size is a fixed set of valid values. Valid values are [27, 28.5, 30, 31.5, 32.5, 33, …, 46, 47, 50, 52, 56]

- The amount must be a discreet positive number. With an upper limit of 1000. If someone is ordering more than 1000 shoes, we need to talk :)

So a possible incoming JSON request can look like this:

{

"name": "Guido",

"shoeSize": "47",

"amount": 5

}With the following as possible implementation:

/** The application API **/

public interface PlaceOrderAPI {

void placeOrder(String name, String size, Integer amount)

}

@RestController()

class PlaceOrderController

{

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

@PostMapping("/PlaceOrder")

String placeOrder(@RequestBody PlaceOrderRequest request)

{

// Do we validate before we invoke the application API?

applicationApi.placeOrder(request.getName(),request.getSize(),request.getAmount());

// or is the implementation of PlaceOrderAPI responsible for this

// And how do we capture and report potential validation errors?

return messages;

}

}

// The same questions for a possible CLI adapter

public class ConsoleAdapter {

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

public ConsoleAdapter(PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi) {

this.applicationApi = applicationApi;

}

String placeOrder(String orderLine) {

// Do we validate before we invoke the application api?

final String[] split = orderLine.split("\\s");

final String name = split[0];

final Integer amount = Integer.parseInt(split[1]);

final String size = split[1];

applicationApi.placeOrder(name, size, amount);

// or is the implementation of PlaceOrderAPI responsible for this

// And how do we capture and report potential validation errors?

return "Success";

}

}Note that all the code used in this blog post can be found in github 1

The incoming data will be sent through our application. So the question is: Where and how do we validate the data request? Before or after the internal application API? And how to report any validation errors?

Where do we validate the data?

Where do we validate the data?

Definitions

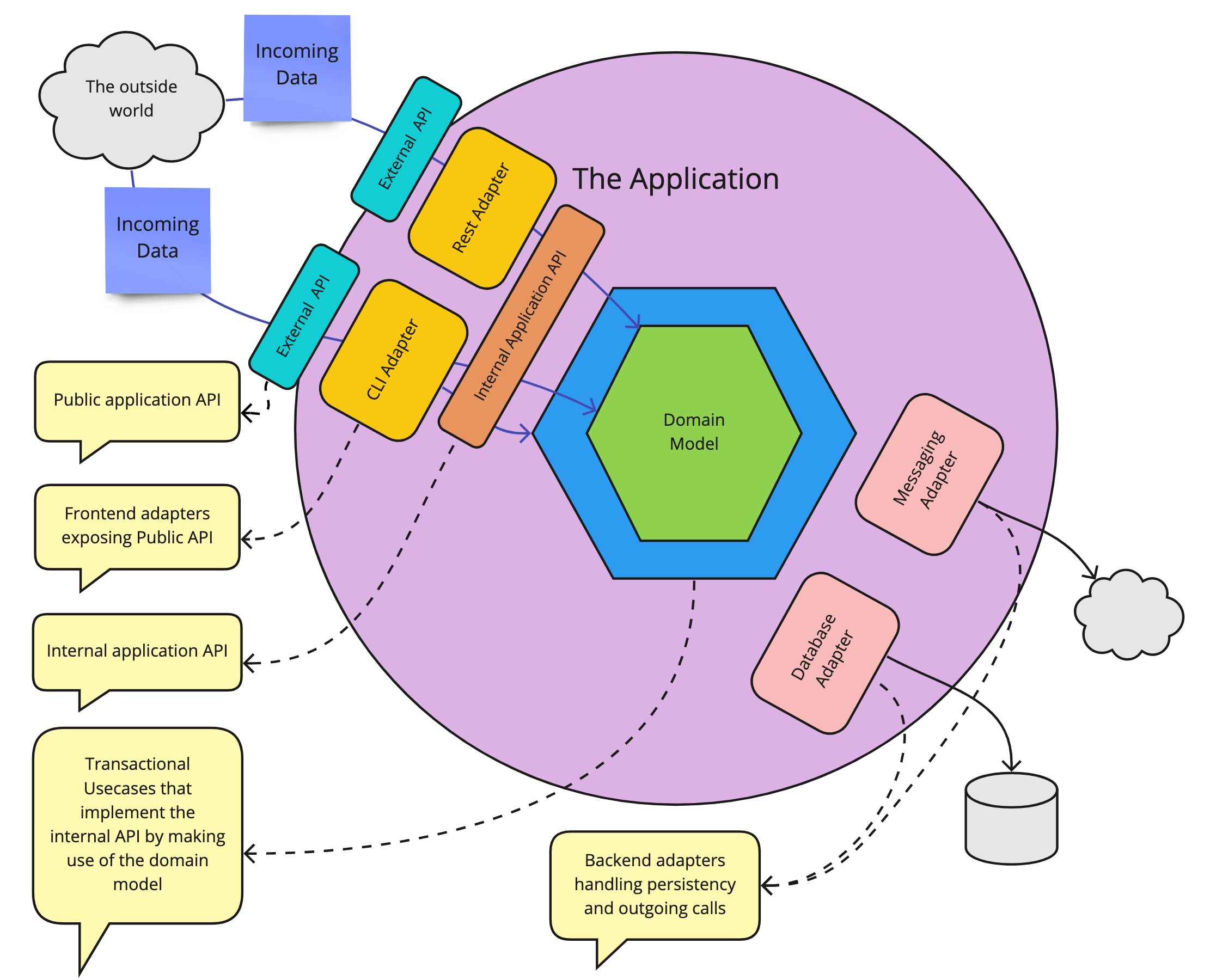

First, we need to start off with some quick definitions, describing the context and high-level architecture in which we will operate. So let’s start with a high-level drawing.

Example application

Example application

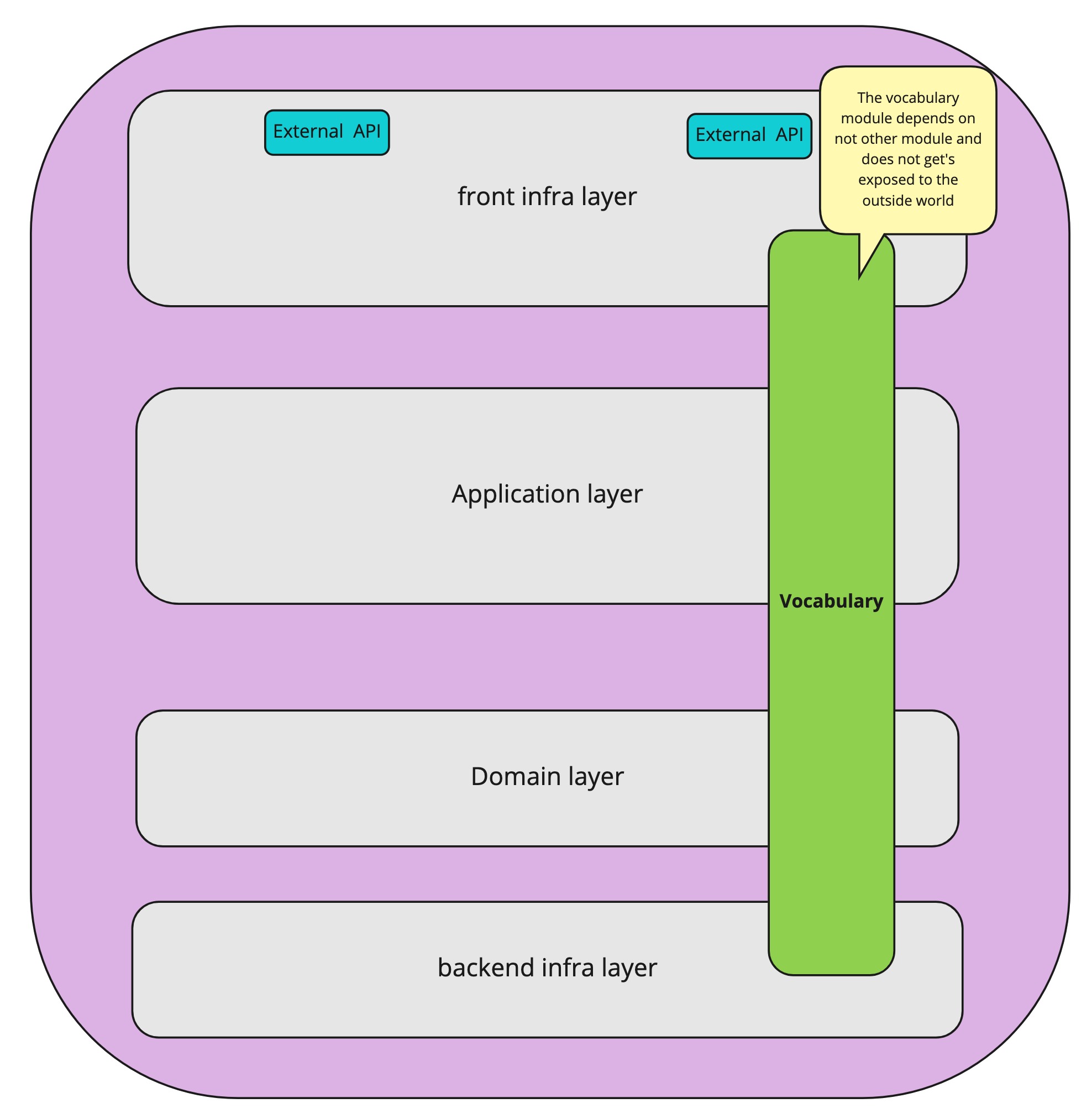

Let’s take as a basis a simple application with a hexagonal architecture. This is not necessary the required architecture, the most important part is the separation between the technically implemented public API that accepts for example JSON, and the internal application API that just talks code and has no knowledge of any external formats. So if you have an internal application API that is separate from the public-facing API, the following discussion is applicable. The discussion we will have will revolve around the following components:

| Name | Definition |

|---|---|

| Layer | A group of modules with a given responsibility |

| Module | A software module. A jar, dll, … |

| API Module | A module containing only contracts and the necessary data structures. This (optional) module serves as a separation between modules, to obtain dependency inversion. |

| Ports | An abstraction/interface that decouples technical implementation concerns from business functionality |

| Adapters | A module that performs a technical translation/action. It implements a port or uses an API module. |

| Application | The application is the whole, of all the different components combined, that make up the application. In the old days, it typically was a single deployable but it doesn’t have to be. And this doesn’t change anything for our story. |

| Public application API | The API that clients use to communicate with us. This is what is available to the outside world. Typically a REST API that can be called by external parties. |

| Internal application API | The internal API module that exposes the functionality that our application offers. This is a pure code API so it can not be exposed directly to the outside world. There is no knowledge of HTTP, Rest, or JSON here. Just plain old code. |

| Use cases | The internal application API is typically implemented by transactional use cases. But those implementation details are hidden by the internal application API. |

| Domain model | Depending on the complexity of your application, there might be a domain model inside that makes it easy to offer the needed functionality. (Note that this has nothing to do with your database model.) But this to is an implementation detail, hidden by the internal application API. |

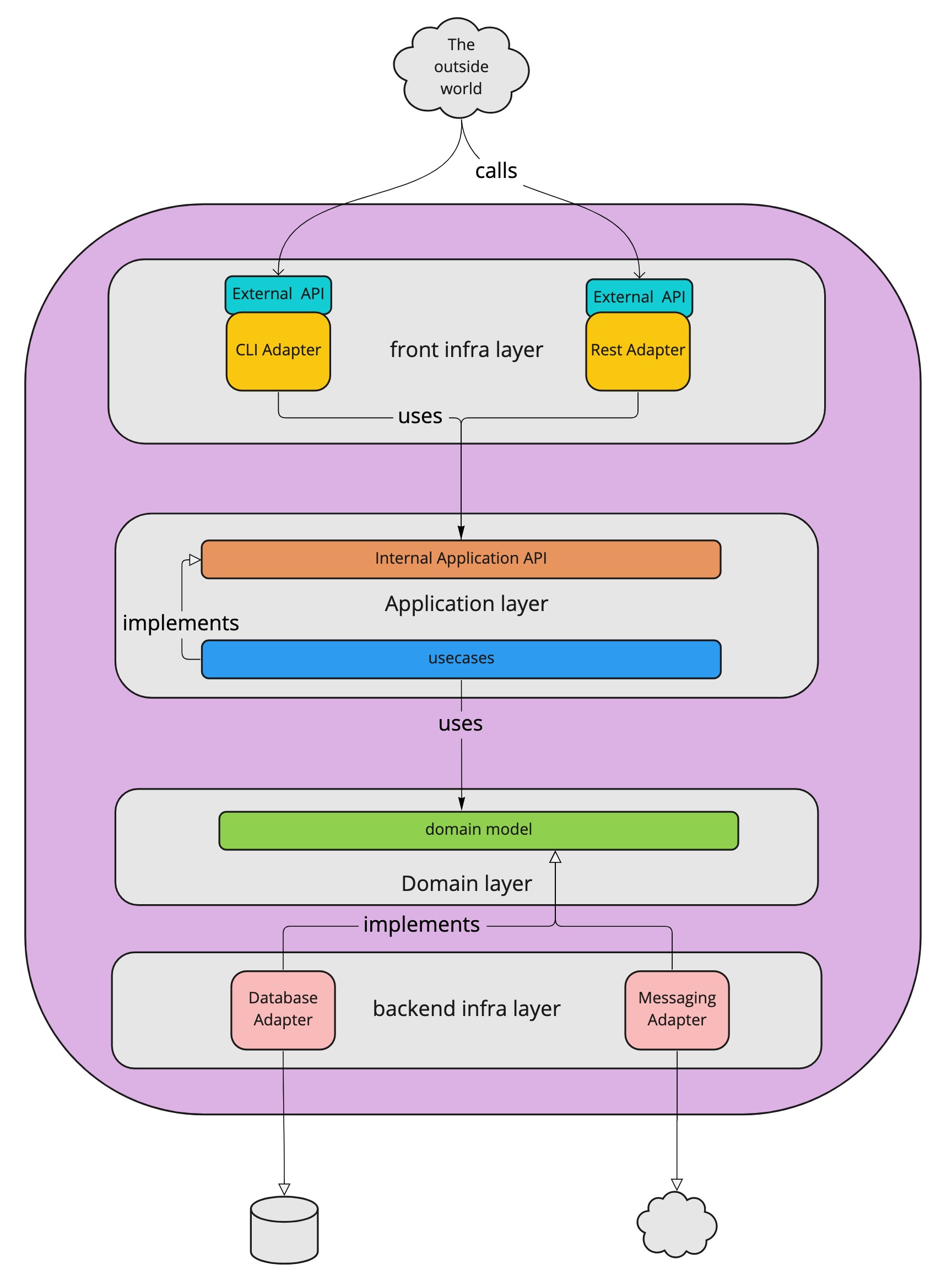

To expose the internal API via the public API, we need an adapter. An adapter is just a module that performs a technical translation. It adapts, as the name says, from one format to another. In a hexagonal architecture, the inbound adapters handle the translation of the exposed public API to the internal API. Important is that we don’t want any business logic inside those adapters because we want to be able for them to be easily interchangeable. A Rest adapter translates the JSON that arrives in the rest controller to concrete calls that are done on the internal API. A CLI adapter could translate command line-level instructions to invocations on the internal application API. Each will have a different translation, but they will arrive, through the internal Application API in the same application. We can easily represent those components as a more classic layered architecture. Where a layer is just a group of modules that can be categorized together.

The application represented as a classic layered architecture

The application represented as a classic layered architecture

Validation requirements

As mentioned in the beginning there are a couple of requirements we impose on the validation.

- 1) The validation logic should not be duplicated. If the logic needs to be modified, we want to change it just in one place.

- 2) There should be no need to do the validation more than once. The applied validation should not get lost. Once something is validated, this information should not get lost.

- 3) The validation should return as much info as possible. If there are 5 violations, please tell them all 5 immediately if possible. No need to force the client to trial and error.

- 4) Validating should be part of the normal flow. Normally, validation can have multiple outcomes. No is a normal answer to a question. No need for the code to throw a fit :-). Which is one of the reasons we do not want to use exceptions as part of our normal validation flow. Exceptions are disruptive technically, but they also make for an unclear API.

No need to throw exceptions when there is a validation error

No need to throw exceptions when there is a validation error

To give some more context to these validation requirements I would like to use a real-world metaphor. Which I think also answers the question “where should the validation occur?”

Security Guards

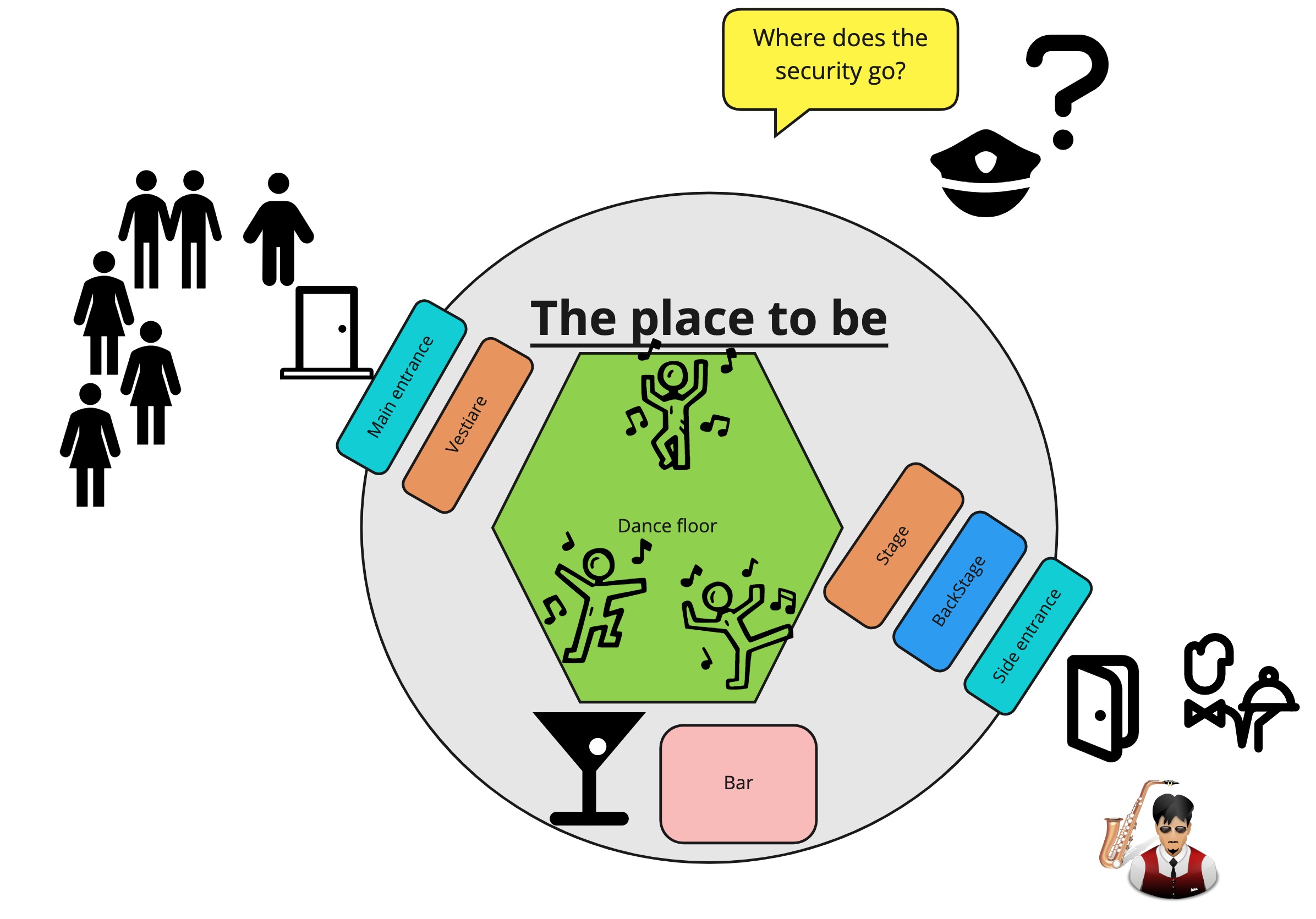

We can look at our application as a very exclusive club, the hottest place in town, where everyone wants to enter. All the cool kids want to spend their Saturday night at our club. Which is great of course. However, this comes with a responsibility. We need to make sure that it is a safe environment for all our clientele. So for people that come in, we need to make sure that

- Everyone is at least 18 years old

- No weapons are smuggled inside

- People that are on the blacklist are not allowed to enter

- Music performers should be on the performer list

Certain constraints are mandatory by law, so we need to enforce those if we want to stay in business. We also want to provide a good experience for the performing artists as well as for our staff. Everyone should want to party with, perform or work for us. Security is a big part of this. Gambling that the only people who walk through the door are all law-abiding citizens is a recipe for disaster. The more well-known our bar is, the more bad elements it will attract. So how would we go about ensuring those constraints without making it a horrible experience?

How to enforce security in our exclusive bar?

How to enforce security in our exclusive bar?

We will want some security in place that enforces the given constraints. We can easily see we have the same requirements present for a security check as with a data validation:

We want the security check applied when people come in. Once people are inside, everyone wants to be sure that they met the conditions set to enter. It’s not the barman’s job to check for weapons. So no additional checks should be necessary, it is perfectly safe inside. It is not possible to just walk inside.

So this answers the question: [Where does validation need to occur?] Before we cross the internal application API boundary. The API guarantees that everything that crosses it is a well-behaving citizen. No validation should happen in the domain model. Because by then it is too late, the party crashers can already be inside.

This leads us to another question: if there is more than one possible entrance, we need to ensure that the same security rules are applied. If the main entrance checks your identity card, but the side entrance does not, then we can all predict what will happen. So the security guards must all enforce the same rules. This maps on the “validation logic should not be duplicated” requirement.

Once people are vetted and identified as Customer, Personel, or Artist, it would be convenient that the people inside can also quickly discern who’s vetted for what. So when someone goes backstage it is immediately clear if they are allowed there. So once inside, we haven’t lost the context of the checks that were made at the entrance. Once you’ve been checked as a registered performer, inside, you don’t need to prove this again. With we can easily do this by handing out badges where needed so that “the applied validation knowledge should not get lost”

Of course, it is also polite that when we refuse people entrance, we let them know why. This maps on the “validation should be part of normal flow” and “validation should return as much info as possible” requirement.

Hopefully, this example gave some context on the why of the requirements we impose on validation. So how does this map to our application?

Enter vocabulary module

Through the security guard metaphor, we determined that we want to perform the validation before we cross the internal application API, which means the validation should occur in the inbound adapter. But given that there is possibly more than one inbound adapter, we now have a problem. Because we determined that we don’t want to duplicate the validation logic across the different inbound adapters. So how do we solve this? How to validate the adapters without duplicating the validation logic across the adapters? By introducing domain primitives grouped in a vocabulary module that can be used by all the inbound adapters.

Enter the vocabulary

Enter the vocabulary

The rules for the vocabulary module are the following

- The vocabulary module only contains immutable, domain primitives

- Everyone inside the application can access the vocabulary module

- The contents of the vocabulary module do not get exposed to the outside world.

Be very careful not to turn this module into a garbage bin that is used to circumvent the imposed dependency limitations of your application architecture. The vocabulary module should contain only domain primitives. The convenience of having a module that everyone can access is very tempting. We do want the vocabulary module to be easily changeable. The internal language and concepts of our application do not need to leak to the outside world. So do not carelessly expose it to the outside world. If you refactor the Vocabulary in your IDE, no external contract should get broken.

A Vocabulary is not a garbage bin

A Vocabulary is not a garbage bin

Domain Primitives

A well-known pattern, especially in DDD context is Value object 2. A value object is an object

- that has no separate identity

- models a conceptual whole

- is immutable

- can be compared with others using value equality

Domain primitives are a special case of value objects. It is a pattern that was named in the excellent book Secure by design 3. So let me just quote from there:

A value object precise enough in its definition that it, by its mere existence, manifests its validity is called a domain primitive. Domain primitives are similar to value objects in Domain-Driven Design. Key differences are that we require invariants to exist and they must be enforced at the point of creation. We’re also prohibiting the use of simple language primitives, or generic types (including null), as representations of concepts in the domain model.

Note that some say that a Value object also has the self-validation property. I follow the original DDD definitions that make the distinction between value objects and domain primitives. If you always let your value objects self-validate: great! Then you are already using domain primitives and your code is more robust for it.

When you are using domain primitives this has the added benefit of avoiding primitives like String and Int in your domain model, avoiding primitive obsession, 4 which I will rant about later. So for now, going back to our example declared in the problem statement, we need a domain primitive for Name, Shoe Size, and Amount that enforces the restrictions we imposed upon them.

The basic Name primitive

public class Name {

public static final int MAX_LENGTH = 100;

public static final int MIN_LENGTH = 2;

public final String value;

private Name(String value) {

this.value = value;

}

public static Name name(String value) {

if (value == null) throw new RuntimeException("Name value may not be NULL");

if (value.isBlank()) throw new RuntimeException("Name value may not be blank");

if (value.length() > MAX_LENGTH) throw new RuntimeException("Name length may not be larger than " + MAX_LENGTH + ". [" + value.substring(0, 20) + "]");

if (value.length() < MIN_LENGTH) throw new RuntimeException("Name length may not be smaller than " + MIN_LENGTH + ". [" + value + "]");

return new Name(value);

}

//toString, equals and hashcode omitted for brevity

}The basic Amount primitive

public class Amount {

private static final int MAX = 1000;

private static final int MIN = 0;

public static Amount ZERO = Amount.mandatoryAmount(MIN);

public static Amount ONE = Amount.mandatoryAmount(1);

public int value;

private Amount(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

public static Amount amount(int value) {

if (isAmountTooSmall(value)) throw new RuntimeException("The amount [" + value + "] must be a larger than " + MIN);

if (isAmountTooLarge(value)) throw new RuntimeException("The amount [" + value + "] must be smaller than " + MAX);

return new Amount(value);

}

private static boolean isAmountTooSmall(int value) {

return value < MIN;

}

private static boolean isAmountTooLarge(int value) {

return value >= MAX;

}

//toString, equals and hashcode omitted for brevity

}The basic ShoeSize primitive

public enum ShoeSize {

SIZE_TWENTY_SEVEN,

SIZE_TWENTY_EIGHT,

SIZE_THIRTY,

SIZE_THIRTY_ONE_HALF,

SIZE_THIRTY_TWO_HALF,

SIZE_FIFTY,

SIZE_FIFTY_TWO,

SIZE_FIFTY_SIX;

static ShoeSize shoeSize(int value) {

switch (value) {

case 27:

return SIZE_TWENTY_SEVEN;

case 28:

return SIZE_TWENTY_EIGHT;

case 315:

return SIZE_THIRTY_ONE_HALF;

//...

case 50:

return SIZE_FIFTY;

default:

throw new RuntimeException("Unknown shoe Size " + value);

}

}

}Code with basic domain primitives be found in github 1

Note that in the intermediate examples above we will still throw exceptions, not bothering yet with validations. But it is already impossible to create incorrect domain primitives. They are immutable, correct, and have an actual meaning relevant to the business. By using these domain primitives in our application API, we have already met validation requirements 1 and 2.

The domain primitives as a basic building block of the internal API

Through our security guard example, we’ve determined that the validation should occur before the internal application API. Inside the adapters. So if multiple adapters make use of the internal application API, then they all map their incoming data request to the application API by making use of the shared domain primitives. Once inside the application, no validation should be necessary anymore. By inserting the validation logic inside our domain primitives, which themselves reside in the vocabulary module that can be used by all the different adapters, there is no need to duplicate that logic anymore. It is encapsulated in the domain primitives and all the adapters can access them. So we’ve obtained the first validation requirement: “The validation logic should not be duplicated”.

/** The application api **/

public interface PlaceOrderAPI {

void placeOrder(Name name, ShoeSize size, Amount amount)

}

@RestController()

class PlaceOrderController

{

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

@PostMapping("/PlaceOrder")

String placeOrder(@RequestBody PlaceOrderRequest request)

{

// We map the data request, specific to this adapter, to our internal, well-known domain primitives.

final Name name = name(request.getName());

final ShoeSize shoeSize = shoeSize(request.getSize());

final Amount amount = amount(request.getAmountName());

//We invoke the API, which is blissfully unaware of any concrete adapter details

applicationApi.placeOrder(name,shoeSize,amount);

// Let's answer this questions next..

return messages;

}

}If we use only domain primitives in our API and inside our application domain we will have fulfilled the second validation requirement [There should be no need to do the validation more than once]. So by using the domain primitives as the basic building block of the internal API, and performing the mapping in the inbound adapters, we have met the first two of our validation requirements

Primitive obsession

Using no data primitives directly is however a controversial statement. I always encounter a lot of resistance when I advocate having no primitives like String passed on through an application. Which has always baffled me. Because if we have not validated before the data came in, it could contain all kinds of garbage. Like a 300-page XML for example. And if we have done some validation on the data primitives but then pass it on still as a data primitive, we have lost the knowledge of that validation. The main safeguard for knowing what is in a data primitive is the variable name. So that variable name should always be correct, clear and hopefully never misinterpreted.

/** Some function inside our application**/

public interface SomeInterface {

//Trust me. I'm a valid businessId and email because I say so.

void createInvoice(String businessId, String email)

}

public class SomeClass {

//Let's hope the context doesn't get lost along the way

void createInvoice(String b, String m)

}This primitive obsession 4, when developing in a type-based system has always seemed very contradictory to me. For the “cost” of a simple type, we could make our code so much safer, hard to misuse, and hard to misinterpret. But the mental cost of creating an extra class seems to outweigh those benefits. Luckily this is my blog post, so let me make my final stance one more time: No Strings in my domain! ;D

Please no primitive obsession

Please no primitive obsession

Compose domain primitives

Note that in a real application, you will want to combine the necessary domain primitives in a higher-level type. Which can have its own validation and constraints. But it relies on the domain primitives as its core building blocks.

public class PlaceOrderCommand{

public final Name name;

public final ShoeSize shoeSize;

public final Amount amount;

//details omitted for clarity

}

/** The application api **/

public interface PlaceOrderAPI {

void placeOrder(PlaceOrderCommand command)

}Validation

Using the basic domain primitives in our adapters we have met the first two of our validation requirements. So how will we tackle the other two requirements? Namely, letting “The validation return as much info as possible” and making “Validating a part of the normal flow”?

Notification pattern

To gather all the validation information in one go we can make use of the notification Pattern5 to gather all the validation messages. In my code example, we will introduce a new class ValidationResult that will capture all the validation messages.

// The validation result as an implementation of the notification pattern

public class ValidationResult {

public static final ValidationResult EMPTY = ValidationResult.builder().build();

public final List<String> messages;

private ValidationResult(Builder b) {

messages = Collections.unmodifiableList(b.messages);

}

public static Builder builder() {

return new Builder();

}

public static ValidationResult create(String singleMessage) {

return ValidationResult.builder().addMessage(singleMessage).build();

}

public ValidationResult merge(ValidationResult other) {

return ValidationResult.builder().addMessages(this.messages).addMessages(other.messages).build();

}

public boolean isEmpty() {

return messages.isEmpty();

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "ValidationResult{" + messages + '}';

}

public static class Builder {

//Basic builder pattern impl

}

}Note that using Strings in the ValidationResult here is ok. We are creating the Strings ourselves, placing them in a primitive with a clear purpose which is to serve as information for the outside world. A validation result should not be crossing the application API inward.

Validation part of normal flow

We want to make validation part of a normal flow. So that the creation of a domain primitive can have two answers. The requested domain primitive or the reasons why the domain primitive could not be created. As explained before this should not be exceptional but part of the normal flow. It is the same principle/pattern as in Railway oriented programming. 6

So let’s introduce a second class, FactoryResult, which contains the result of the factory or the reasons why it could not be created.

public class FactoryResult<T> {

private final T createdInstance;

private final ValidationResult validationResult;

private FactoryResult(T createdInstance, ValidationResult validationResult) {

if (createdInstance != null && validationResult != null) throw new RuntimeException("A factoryResult may not have a createdInstance and errorMessages");

if (createdInstance == null && ((validationResult == null) || validationResult.isEmpty()))

throw new RuntimeException("A factoryResult must have a createdInstance or errorMessages");

this.createdInstance = createdInstance;

this.validationResult = (validationResult == null) ? ValidationResult.EMPTY : validationResult;

}

public static <T> FactoryResult<T> success(T t) {

return new FactoryResult<T>(t, null);

}

public static <T> FactoryResult<T> failure(List<String> errorMessages) {

return new FactoryResult<>(null, ValidationResult.builder().addMessages(errorMessages).build());

}

public static <T> FactoryResult<T> failure(String... errorMessages) {

return new FactoryResult<>(null, ValidationResult.builder().addMessages(Arrays.stream(errorMessages).toList()).build());

}

public static <T> FactoryResult<T> createIfValid(ValidationResult validationResult, Supplier<T> factoryMethod) {

if (validationResult.isEmpty()) return FactoryResult.success(factoryMethod.get());

else return FactoryResult.failure(validationResult);

}

public static <T> FactoryResult<T> failure(ValidationResult validationResult) {

return failure(validationResult.messages);

}

public void onSuccess(Consumer<T> happyPathHandler) {

if (hasValidInstance()) {

happyPathHandler.accept(createdInstance);

}

}

public void onFailure(Consumer<List<String>> errorHandler) {

if (hasNoValidInstance()) {

errorHandler.accept(validationResult.messages);

}

}

public T mandatoryValidInstance() {

if (hasNoValidInstance()) throw new RuntimeException("A valid instance was expected but there were unexpected errors " + validationResult.toString());

else return createdInstance;

}

public ValidationResult validationResult() {

return validationResult;

}

private boolean hasValidInstance() {

return createdInstance != null;

}

private boolean hasNoValidInstance() {

return createdInstance == null;

}

}We will place these two classes also in the Vocabulary module. ( Details on github ) You could argue that they are not part of the domain but are a mini-validation framework. But since they are two immutable classes that are part of our normal flow I consider them domain primitives and part of the Vocabulary.

Domain Primitives with Validation

Using the ValidationResult and FactoryResult, we can modify our earlier domain primitives so they no longer throw exceptions on a validation violation.

The Name primitive with validation

public class Name {

//...

private Name(String value) {

this.value = value;

}

//No exceptions were thrown during the making of this domain primitive

public static FactoryResult<Name> name(String value) {

if (value == null) return failure("Name value may not be NULL");

if (value.isBlank()) return failure("Name value may not be blank");

if (value.length() > MAX_LENGTH) return failure("Name length may not be larger than " + MAX_LENGTH + ". [" + value.substring(0, 20) + "]");

if (value.length() < MIN_LENGTH) return failure("Name length may not be smaller than " + MIN_LENGTH + ". [" + value + "]");

return success(new Name(value));

}

//...

}The Amount primitive with validation

public class Amount {

//...

public int value;

private Amount(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

//No exceptions were thrown during the making of this domain primitive

public static FactoryResult<Amount> amount(int amount) {

final ValidationResult validationResult = validate(amount);

return FactoryResult.createIfValid(validationResult, () -> new Amount(amount));

}

//...

}The ShoeSize primitive with validation

public enum ShoeSize {

SIZE_TWENTY_SEVEN,

SIZE_TWENTY_EIGHT,

SIZE_THIRTY,

SIZE_THIRTY_ONE_HALF,

SIZE_THIRTY_TWO_HALF,

SIZE_FIFTY,

SIZE_FIFTY_TWO,

SIZE_FIFTY_SIX;

//No exceptions were thrown during the making of this domain primitive

static FactoryResult<ShoeSize> create(int value) {

switch (value) {

case 27:

return FactoryResult.success(SIZE_TWENTY_SEVEN);

case 28:

return FactoryResult.success(SIZE_TWENTY_EIGHT);

case 315:

return FactoryResult.success(SIZE_THIRTY_ONE_HALF);

//...

case 50:

return FactoryResult.success(SIZE_FIFTY);

default:

return FactoryResult.failure("Unknown shoe Size " + value);

}

}Putting it all together

Now that the domain primitives in our shared Vocabulary module are well-behaved and return a proper response, no matter the outcome of the creation request, all the incoming adapters can map their incoming data requests to the internal application API. Which is constructed from domain primitives. In practice this looks like this:

public class RestController {

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

public RestController(PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi) {

this.applicationApi = applicationApi;

}

@PostMapping("/PlaceOrder")

String placeOrder( @RequestBody PlaceOrderRequest request) {

// We map the data request, specific to this adapter, to our internal, well-known domain primitives.

// For simplicity we perform the mapping directly in the controller

// For more complex cases, it would be better to extract the mapping logic to a separate mapper class

final FactoryResult<Name> name = Name.name(request.getName());

final FactoryResult<ShoeSize> shoeSize = ShoeSize.create(request.getSize());

final FactoryResult<Amount> amount = Amount.amount(request.getAmount());

final ValidationResult validationResult = name.validationResult().merge(shoeSize.validationResult()).merge(amount.validationResult());

if (validationResult.isEmpty()) {

//We invoke the api, who is blissfully unaware of any concrete adapter details

applicationApi.placeOrder(

name.mandatoryValidInstance(),

shoeSize.mandatoryValidInstance(),

amount.mandatoryValidInstance());

return "Success";

} else {

return validationResult.toString();

}

}

}Now we have met all of our initially imposed validation requirements. No exceptions are thrown and all the necessary information is available in one go. And we have an expressive Vocabulary and application-api on top of it.

A little bit of refactoring

The code above was kept as is for clarity. But of course, we want to refactor it a bit more. Extracting the mapping logic outside the adapters, placing the arguments from the API together in a composite… After a bit of refactoring it could look as simple as this:

public class RestController {

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

public RestController(PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi) {

this.applicationApi = applicationApi;

}

@PostMapping("/PlaceOrder")

String placeOrder( @RequestBody PlaceOrderRequest request) {

final FactoryResult<PlaceOrderCommand> result = PlaceOrderMapper.mapRequestToCommand(request);

return result.process(this::placeOrder, this::validationErrorsToMessage);

}

private String placeOrder(PlaceOrderCommand command) {

applicationApi.placeOrder(command);

return "Success";

}

private String validationErrorsToMessage(ValidationResult x) {

return x.messages.toString();

}

}

//The mapping logic is moved to separate mapper

final class PlaceOrderMapper {

//...

static FactoryResult<PlaceOrderCommand> mapRequestToCommand(PlaceOrderRequest request) {

return PlaceOrderCommand.newFactoryResultBuilder()

.withShoeSize(ShoeSize.shoeSize(request.getSize()))

.withName(Name.name(request.getName()))

.withAmount(Amount.amount(request.getAmount()))

.build();

}

}The Console controller would look similar with the mapping logic extracted:

public class ConsoleAdapter {

private final PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi;

public ConsoleAdapter(PlaceOrderAPI applicationApi) {

this.applicationApi = applicationApi;

}

String placeOrder(String orderLine) {

final FactoryResult<PlaceOrderCommand> result = PlaceOrderParser.parsePlaceOrderCommand(orderLine);

return result.process(this::placeOrder, this::validationErrorsToMessage);

}

private String validationErrorsToMessage(ValidationResult x) {

return x.messages.toString();

}

private String placeOrder(PlaceOrderCommand command) {

applicationApi.placeOrder(command);

return "Success";

}

}

final class PlaceOrderParser {

//..

static FactoryResult<PlaceOrderCommand> parsePlaceOrderCommand(String orderLine) {

final String[] split = orderLine.split("\\s");

if (split.length < 3) return FactoryResult.failure("Unable to parse command. Expected three arguments");

return PlaceOrderCommand.newFactoryResultBuilder()

.withAmount(Amount.amount(split[2]))

.withName(Name.name(split[0]))

.withShoeSize(ShoeSize.shoeSize(split[1]))

.build();

}

}The adapters are only responsible for translating their own specific format to the common application-api and back. They contain no business logic and validation messages are part of the normal flow.

Conclusion

In this post, I have tried to make the case that by being more explicit in our internal API, and by using domain primitives instead of primitive data types, we not only make our code more expressive but harder to misuse. We also gain a well-secured, well-behaving application that is more resilient to bugs and harder to misuse by its clients.

I have taken the purest, most strict approach as how I handle this problem. As always, this is my opinion and in practice there are some nuances and gradations that one could apply. But we most definitely should get over this Primitive obsession thing :-)

References