The importance of the dependency inversion principle

The dependency inversion principle (DIP) is a well known principle and one of the five SOLID principles. It is at the heart of a lot of software design patterns, frameworks and architectures. This article will try to connect some dots and hopes to provide some additional insight into the application of this core principle.

The principle

The DIP principle states the following:

High level policy should not depend on low level details, instead, both should depend upon abstractions. Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.

In essence the principle advocates two things. First it states that important things should not depend on details. Which hopefully makes a lot of sense. It also states that these concerns of different importance should be loosely coupled from each other. This should be done by using meaningful abstractions as the middleman.

This may sound simple in theory but it is often difficult to distinguish the important things from the unimportant ones. Also it requires discipline and insight to separate the two properly.

Inverting dependencies

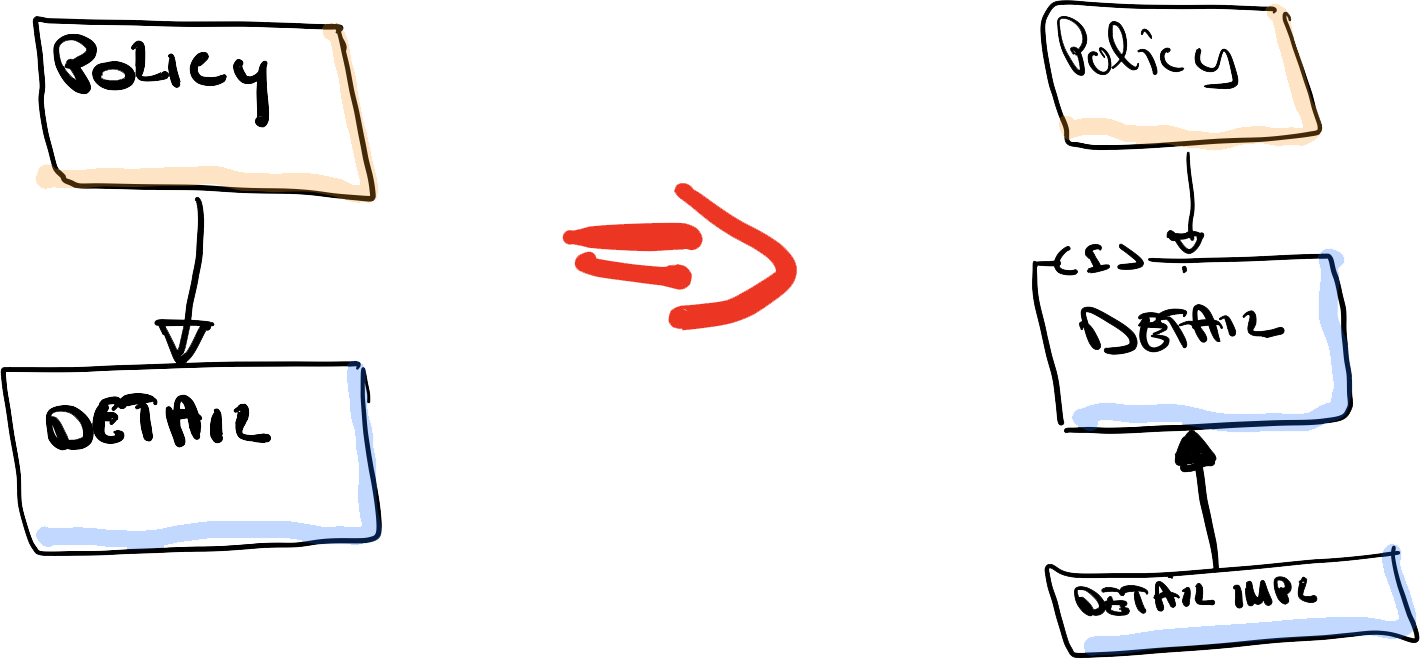

Applying the dependency inversion principle starts by introducing an abstraction between the high level policy and the low level detail. This abstraction removes the direct dependency on the details, decoupling it and thus allows for easier re-use of the important functionality in the policy. By introducing an abstraction, we allow the low level details, which are typically far more volatile then the high level policy, to be interchangeable, without requiring changes to the high level policy.

We call this dependency inversion because the high level policy no longer has a uses relationship with the low level policy but the low level policy now has an implements relationship on the abstraction.

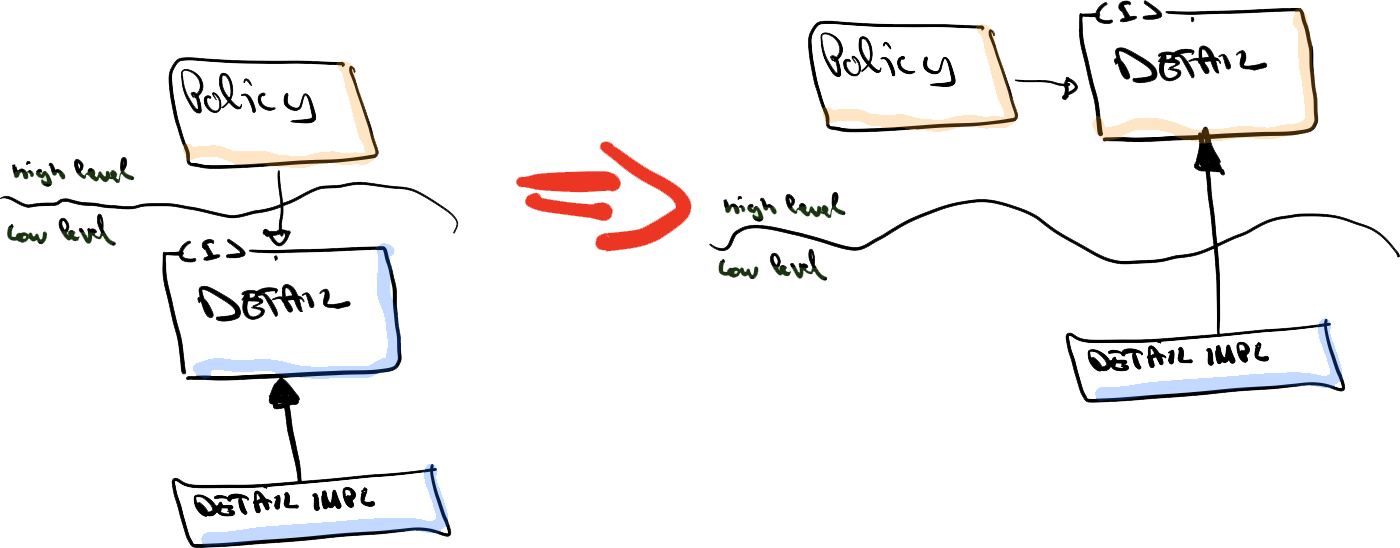

This implies that the high level policy and the abstraction reside on the same level. Which brings us to our next topic.

Where to put the abstraction?

Who owns the abstraction upon which the high level policy depends and why? Where does the abstraction belong? The answer is actually already given in the definition of DIP. When we are ‘inverting’ the dependency, we are in essence going from a high level policy that ‘uses’ a low level detail (the dependency) to a situation where the high level policy ‘uses’ an abstraction and the low level policy now has the inverted relation “implements” (the inverted dependency) towards the abstraction. Since our goal was for the high level policy to no longer depend on the low level, the abstraction belongs with the high level policy.

There is also the cohesive aspect of “reason to change”. Why would the abstraction need to change? Because the one that uses it, requires something different from it. It is the high level policy that has the uses relation to the abstraction. Therefore they belong together.

The low level policies, the details, are just plugins to our important policies.

“Dependency inversion” is not “Dependency injection”

Many developers confuse the dependency inversion principle with dependency injection (DI). But these are two separate things. Dependency injection is a technique whereby one supplies the dependencies to an object. The intent behind dependency injection is to achieve separation of concerns between the construction and the use of objects. It states nothing on the relative importance between those objects or if an abstraction is used.

Dependency injection in itself is a form of the broader technique of inversion of control (IOC). IOC in itself can support DIP. But it is not because we use DI or IOC that we are necessarily applying DIP. No framework can help us determining what is high level and what is low level. Nor with defining the proper abstraction to separate the two.

When trying to apply DIP inside our codebase, we can ask ourselves: “Who instantiates the low level implementation of the abstraction if it’s located in an an other module? Using an IOC container, this is an easy problem. The IOC container could create the instance of the low level module and inject it where necessary. So an IOC container makes it really easy to inject low level details into our high level modules. But we still need to provide the proper abstractions ourselves. And we are still responsible for placing the abstractions in the correct location, next to the high level policy.

So is an IOC container required when one wants to apply DIP? Of course not. We just need some sort of “main” module that wires our application together. The “main” is able to access all the necessary objects and wire them together. This is a purely technical affair that we could handle ourselves but it is a solved problem for which we often prefer the use an IOC. But using a IOC does not guarantee that DIP is applied. It is up to us to define the proper architectural boundaries and policy separations. So DI does not imply DIP and vice versa. Separate things.

Using a IOC does not guarantee that DIP is applied

The principle applied

The repository pattern

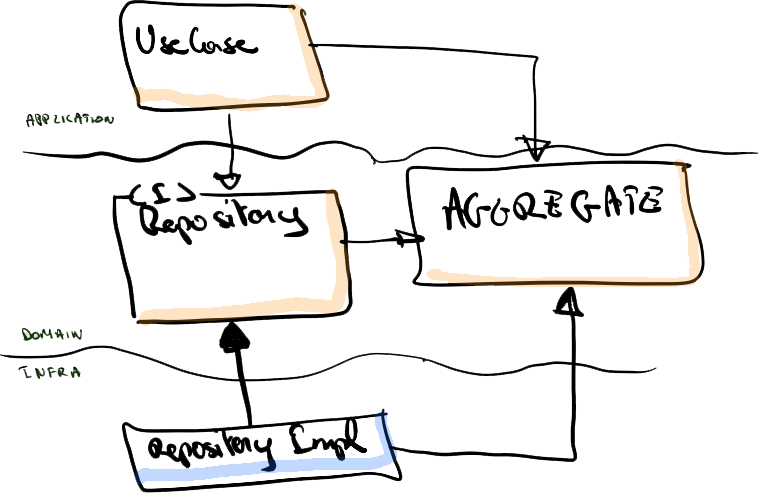

Looking at the repository pattern, as originally coined by Eric Evans, we can clearly see that it’s a fine example of the dependency inversion principle. The pattern states that an abstraction should be created which is free of technical details, and should preferably look a lot like a collection interface. The abstraction should be implemented in the infrastructure layer where all the technicalities of dealing with a persistent store should be hidden. From the domain perspective, we are talking with a collection-like interface to store the aggregates.

Placing this abstraction inside the domain layer, close to its consumers, ensures that the domain layer is guarded from any changes to the low level infrastructure code. It also makes perfect sense from a usability standpoint since the repository is defined in the domain language. The repository abstraction should be clean, no technical details should leak through the api.

As a side note, the idea of the repository pattern is to abstract away the persistency details. We obtain domain concepts from a repository. Not low level data where we still need to attach meaning to. If we obtain the aggregate from memory, a relational db, a document db or an event sourced system, those are low level details. A repository is not just a DAO.

A repository is not a data access object

Ports and adapters architecture.

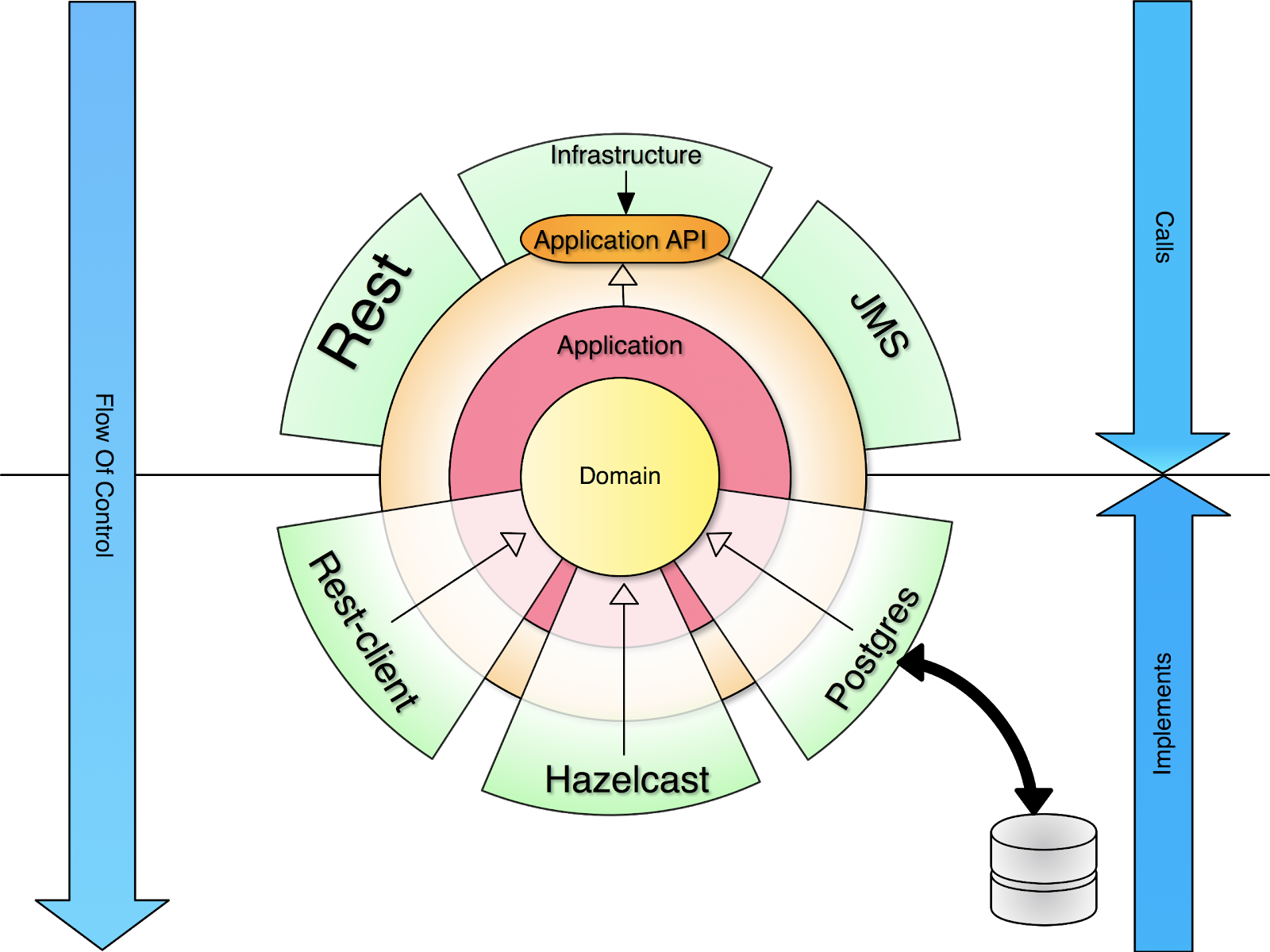

When applying the dependency inversion principle on the architectural layers of your application, we’re bound to end up with a hexagonal architecture also called ports and adapters or as Uncle bob calls it: Clean Architecture.

This architectural style applies DIP as an additional restriction on the multiple layers of an application. As a result all dependencies point towards the centre where the high level policy logic should reside. Therefore the centre is where we hope to find the domain model, the core functionality of the application. Achieving DIP in a layered architecture is achieved by creating abstract interfaces for the low level details. These low level details are typically called the adapters and sit at the boundary of your system. The abstractions are called the ports and are part of the domain layer.

DIP in Kubernetes

In the Container Orchestrator Kubernetes we encounter Ingress which is an API object that manages external access to the services in a cluster. So an Ingress is an abstraction that provides a functionality to services. In Kubernetes, services are an abstraction themselves that represent a logical set of pods. So on both sides of the spectrum we have abstractions communicating with each other. These abstractions decouple the details of pods and external access. Allowing the high level policies from K8 to work without being hindered by the details.

Conclusion

The Dependency inversion principle is an important principle that helps us to decouple the importance things from the details. It protects us from a ripple effect from changes inside low level modules. Because it neatly separates different concerns and allows the important concerns to take centre stage, our software can easily be adapted and understood. It enables the core of our software, the important stuff, to endure and survive the frequent changes in the more volatile lower level modules. It is however not an easy principle to apply. It requires thought and discipline to apply it correctly and consistently. But the benefits far outweighs the effort required.

DIP enables the core of our software to endure and survive the frequent changes of the more volatile lower level parts of the software.