The anemic domain model

In this blog post i will discuss the anemic domain model pattern in the context of an object oriented language. I’ll explain what the anemic domain model is, what it isn’t, how i view it. I’ll make use of a code example written in java and tested with cucumber.

Anemic domain model

What is the anemic domain model?

The anemic domain model is a pattern for structuring a domain model. It separates the objects in the domain model into service objects and data objects. As a result the data objects class diagram looks like a model with all the necessary relationships, however they contain only the data and getters and setters methods. The logic that operates on that data is not present in the data object but resides in the service objects. The service objects are thus the opposite and complementary to the data objects. Obviously service objects contain no data but they operate on the data stored in the data objects. They contain all the logic and behaviour of the model. It is often linked to Domain Driven Design due to domain model in its name. But it is not necessary linked to DDD.

Where does the name come from?

It is called an anemic (pale, weak) domain model because it looks like an actual domain model but it’s not. An actual domain model is a conceptual model of the problem domain that incorporates both behavior and data. By creating data objects and service objects but no real objects with behaviour there is no real model. Hence the term anemic domain model. The classes are there, it looks like they have meaningful relations. But it is a pale imitation of the real thing.

Is it bad?

If we look at the definition of an object then it clearly states that an object contains encapsulated data and procedures grouped together. Since the anemic domain model pattern separates data and behaviour this conflicts with the original intent of OO. That’s why it is considered by many to be an Anti-pattern.

The paperboy example

Paperboy description

As an example for the anemic domain model we will use the paperboy example. The paperboy is an example that is often used to illustrate the law of demeter. 1 We have created a small code base implementation of the paperboy that can serve as an illustration of what an anemic domain model is. We will use it to illustrate what the disadvantages of the anemic domain model are and how can it be made into a real domain model. For those in a hurry, you can always look directly to the code base. 2

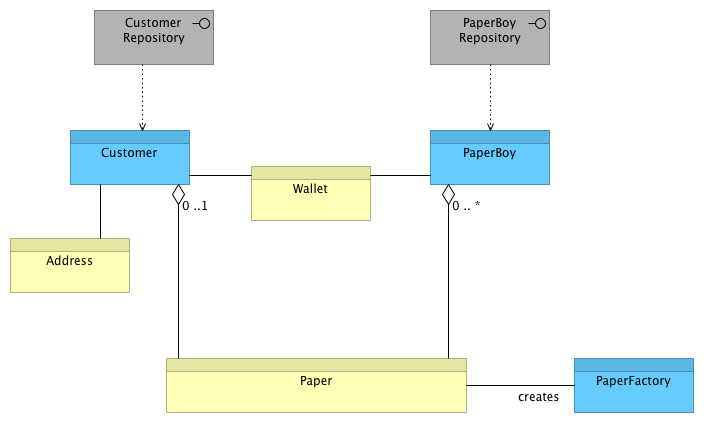

We will get into more detail on this example but for now here is the UML diagram of the domain model.

From this model you can deduce what the problem domain is for this application. Obviously it’s about paperboys and their customers. Both have exactly one wallets and both have zero or one paper. So the intent of the domain is most likely for the paperboy to sell papers to its customers upon which money should be transferred from the customer to the paperboy wallet. All this seems obvious by the class diagram itself but as we will see, it is but a pale, anemic reflection of a real domain model.

The paperboy use cases

The simplest acceptance test for the paperboy example describes the required functionality. More acceptance tests can be found in the code example.

Scenario Outline: Single customer delivery

| Given | a single customer with CustomerStartMoney eur |

| And | a single paperboy |

| And | the price of a paper is PaperPrice eur |

| When | the paper is delivered |

| Then | the paperboy sold NrOfPapersSold newspapers for a total of Revenue eur |

| And | the single customer has CustomerEndMoney eur left and owns a paper state is PaperState |

Examples

| CustomerStartMoney | PaperPrice | NrOfPapersSold | Revenue | CustomerEndMoney | PaperState |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 eur | 1 eur | 0 | 0 eur | 0 eur | false |

| 1 eur | 1 eur | 1 | 1 eur | 0 eur | true |

| 2 eur | 1 eur | 1 | 1 eur | 1 eur | true |

| 0 eur | 2 eur | 0 | 0 eur | 0 eur | false |

| 1 eur | 2 eur | 0 | 0 eur | 1 eur | false |

| 2 eur | 2 eur | 1 | 2 eur | 0 eur | true |

For those unfamiliar with Gherkin3 a short explanation of the above scenario. Each row of the table contains the values for the variables in the scenario. For the given scenario 6 tests, corresponding to the 6 rows in the table, are run.

The paper boy as an anemic model

Anemic model code

Below you will find the paperboy anemic model. The complete code can be found in the online code base. The dependencies for the code has been kept to a minimum. The production code only has a dependency on guava for its handy collection utilities. So just plain old java code from here on out.

public class PaperBoy {

private Wallet wallet;

private List<Paper> papers;

public Wallet getWallet() {

return wallet;

}

public void setWallet(Wallet wallet) {

this.wallet = wallet;

}

public List<Paper> getPapers() {

return papers;

}

public void setPapers(List<Paper> papers) {

this.papers = papers;

}

}

public class Customer {

private Wallet wallet;

private Paper paper;

private Address address;

public Address getAddress() {

return address;

}

public void setAddress(Address address) {

this.address = address;

}

public Wallet getWallet() {

return wallet;

}

public void setWallet(Wallet wallet) {

this.wallet = wallet;

}

public Paper getPaper() {

return paper;

}

public void setPaper(Paper paper) {

this.paper = paper;

}

}

public class Wallet {

private MonetaryAmount money;

public MonetaryAmount getMoney() {

return money;

}

public void setMoney(MonetaryAmount money) {

this.money = money;

}

}Anemic model delivery logic code

public class PaperBoyRoundService {

public void deliverPapers(PaperBoy paperBoy, Set<Customer> customers) {

customers.stream()

.forEach(customer -> deliverPaper(paperBoy, customer));

}

private void deliverPaper(PaperBoy paperBoy, Customer customer) {

final MonetaryAmount unitPriceOfPaper = getPaper(paperBoy).getUnitPriceOfPaper();

if (customer.getWallet().getMoney().isGreaterThanOrEqualTo(unitPriceOfPaper)) {

customer.setPaper(getPaper(paperBoy));

paperBoy.getPapers().remove(0);

customer.getWallet().setMoney(customer.getWallet().getMoney().subtract(unitPriceOfPaper));

paperBoy.getWallet().setMoney(paperBoy.getWallet().getMoney().add(unitPriceOfPaper));

}

}

private Paper getPaper(PaperBoy paperBoy) {

if (paperBoy.getPapers().isEmpty())

throw new RuntimeException(paperBoy + " is out of papers!");

else

return paperBoy.getPapers().get(0);

}

}Evaluation of the anemic domain model

Rules violated in the anemic domain model

I. Tell don’t ask

Tell objects what you want them to do, don’t take their state and make the decisions for them. It is clear that in the deliverPaper method the objects are asked for their state and we make a decision for them. This breaks encapsulation. This is inherent to the anemic domain model pattern. A service object will always ask an object for it’s state and then act on it, rather then telling an object to do something.

Martin Fowler:

Many people find tell-don’t-ask to be a useful principle. One of the fundamental principles of object-oriented design is to combine data and behavior, so that the basic elements of our system (objects) combine both together. This is often a good thing because this data and the behavior that manipulates them are tightly coupled: changes in one cause changes in the other, understanding one helps you understand the other. Things that are tightly coupled should be in the same component. Thinking of tell-don’t-ask is a way to help programmers to see how they can increase this co-location.

Alec Sharp (Pragmatic programmers)

Procedural code gets information then makes decisions. Object-oriented code tells objects to do things.

II. Law of Demeter

Simply put the law of Demeter boils down to objects only requiring limited knowledge about other units. They should only communicate with their immediate friends. Where the PaperBoyRoundService should just say “paperboy do your rounds”. The deliverPaper method should just say “paperboy deliver to this customer”. We see in the deliverPaper method that the service needs to know about the customer’s wallet and that the wallet should contain the money for the paper. The service also needs to know all the internals of the PaperBoy class in order to it’s work. The weird thing about this implementation is that we need to give the customers wallet to the paperboy who will then take out the required money from the wallet. Think of this example next time you are at a grocery store.

III. Single responsibility principle

A class should have only one reason to change, a single responsibility. The single responsibility principle aims to achieve loosely coupled and highly cohesive classes. The logic concerning paperboy and customer is scattered. Apart from the fact that the PaperBoyRoundService shouldn’t even exist (See later code), delivering a paper may be one responsibility in the current simple code. But we can easily add a milkman and a DeliverMilkService. The fact that a paperboy delivers paper, the milkman delivers milk and the customer buys something are three different responsibilities. If tomorrow the customer no longer has a wallet but uses his old socks to store his money, we need to change a lot of services. There are many reasons to change the DeliverService, the code is highly coupled since all the internals are exposed.

Code smells in the anemic domain model

A lot of the classic code smells can be found in an anemic domain model.

I. Feature envy

When a method accesses most of another object’s data to do it’s job.

customer.getWallet().getMoney()II. Message chains or Train wrecks

Long chained methods that make it hard to comprehend what happens. The fun realy starts when you have a nullpointer on that line.

customer.getWallet().setMoney(customer.getWallet().getMoney().subtract(unitPriceOfPaper));

paperBoy.getWallet().setMoney(paperBoy.getWallet().getMoney().add(unitPriceOfPaper));Of course the above paper boy delivery logic can be written differently by extracting some variables. Reducing the length of the calls but increasing the local variables and number of lines. The real problem still remains, we have just hidden it a bit.

public class PaperBoyRoundService {

//...

private void deliverPaper(PaperBoy paperBoy, Customer customer) {

final Paper paper = getPaper(paperBoy);

final MonetaryAmount unitPriceOfPaper = paper.getUnitPriceOfPaper();

final Wallet customerWallet = customer.getWallet();

final MonetaryAmount beforeBuyCustomerMoney = customerWallet.getMoney();

if (beforeBuyCustomerMoney.isGreaterThanOrEqualTo(unitPriceOfPaper)) {

customer.setPaper(paper);

paperBoy.getPapers().remove(0);

final MonetaryAmount afterBuyCustomerMoney = beforeBuyCustomerMoney.subtract(unitPriceOfPaper);

customerWallet.setMoney(afterBuyCustomerMoney);

final Wallet paperBoyWallet = paperBoy.getWallet();

final MonetaryAmount beforeBuyPaperBoyMoney = paperBoyWallet.getMoney();

final MonetaryAmount afterBuyPaperBoyMoney = beforeBuyPaperBoyMoney.add(unitPriceOfPaper);

paperBoyWallet.setMoney(afterBuyPaperBoyMoney);

}

}

}III. Hybrids

In Clean Code uncle Bob discusses train wrecks and hybrids as code smells. He also makes the clear distinction between two types of classes.

Objects expose behaviour and hide data. Data structures expose data and have no significant behaviour

Using one for the other results in one of his code smells. See Clean code, Chapter 6: Objects and data structures

IV. Mutable state

Exposing the mutable data of your ‘model’ makes code very fragile, It is for example very vulnerable to null pointers. I for one do not want my application to crash. A null pointer to me is the result of a developer being lazy. By allowing other entities to mutate your state the code will be full with null checks. If something can never become null, you don’t need to check it every time.

V. No invariants

By exposing all our data a class can not maintain an invariant over its content. If we look at our example an invariant for a customer would be that he may have lost money without obtaining a paper. For the paperboy it is the opposite. He may have lost a paper without having received money. These two invariants are maintained in the paperboyService.

public class PaperBoyRoundService {

//...

private void deliverPaper(PaperBoy paperBoy, Customer customer) {

//...

customer.setPaper(paper);//part 1 of Invariant 1

paperBoy.getPapers().remove(0);//part 1 of Invariant 2/

//...

customerWallet.setMoney(afterBuyCustomerMoney);//part 2 of Invariant 1

//...

paperBoyWallet.setMoney(afterBuyPaperBoyMoney); //part 2 of Invariant 2

}

}Appeal to authority against the anemic domain model

Hopefully I made my case that the anemic domain model has several bad properties. But let’s continue the argument against the anemic domain model by making an appeal to authority.

The fundamental horror of this anti-pattern is that it’s so contrary to the basic idea of object-oriented design; which is to combine data and process together. The anemic domain model is really just a procedural style design. What’s worse, many people think that anemic objects are real objects, and thus completely miss the point of what object-oriented design is all about.

Why are domain models so often anemic? Simple answer: They start with databases. When we start with a database, we are starting with data structures that have no behavior. Our thought processes are related to how data should be represented, and not how behavior should be represented. This causes us to create elegant sets of interconnected data structures that represent the persistent state of the system. It does not cause us to create elegant sets of interconnected behaviors that represent the function of the system. This is unfortunate because the reason we program computers is to make them behave. Programming is the art of describing behavior to a machine.

“Anemic domain model anti-pattern” should be called “Not supposed to be a domain model just persisting some stuff pattern”

If you are using a domain model in an object oriented way to help you in the managing of complexity it is absolutely an anti-pattern for you to be seeing an anemic domain model. …. although the “anemic domain model” is called a domain model. It is not really a domain model at all it is in fact transaction script.”

To be fair i quoted Greg rather selectively here. Because in the blog post he makes the case for when the anemic domain model is actually good. But i will address that in the next topic.

Advantages of the anemic domain model

So far i have given several disadvantages of the anemic domain model. But is it all bad? As with everything, the correct answer is: it depends.

Let me refer back to Greg Young’s blog post where he mentions the disadvantages of the anemic domain model. The topic of the blog post however was not against but for the anemic domain model. Greg was making the case when it can be appropriate to choose for the anemic domain model.

The following requirements might be a reason to choose for the anemic domain model.

- You want a layered architecture.

- Your domain is not extremely complex.

- Your team is not highly functional in object oriented design and analysis.

- You would otherwise even consider a simpler model such as Transaction script 8 but feel that you can benefit from things such as further testability.

If your domain logic is so simple that it can be contained in a few clear functions that are not constantly calling each other then it can be ok to program in a procedural style in a object oriented language. All the logic is contained in a simple function, it is very simple understandable and maintainable.

The problems start to occur when we fast forward the code base two years in the future. If the domain logic has grown so that it is no longer the case that all the logic is contained in one place. Nor is it simple understandable or maintainable. Since the data and logic are separated in an anemic domain model and due to the increase in logic it is now very hard to determine which path was taken to reach a certain point in the code base. Or to determine what the state of the data is.

Imagine that in the paperboy example we add our milkman, garbage man, paperboy capacity, customer wages. It would be very hard to make that application bug free. Let alone determine the cause of money that went missing.

Can you guarantee that when the domain starts to become more complex, you can still move away from the anemic domain model? Of will you end up with the classic bug ball of mud?

My opinion

After creating the paperboy code i really want to publicly state my firm dislike of the anemic domain model. The amount of bugs and null pointers i encountered trying to make the simple paperboy anemic domain model pass the acceptance tests was just frustrating. All the things that can, and eventually always will, go wrong when everything is mutable and the logic is spread out is frustrating. The basic paperboy example only contains a single service. Consider adding the milk man, garbage man, paper boy limited capacity… Adding this extra functionality to the example would increase the likelihood for bugs even more. All the time that is lost on debugging, in getting it to work… Time you could have spent doing interesting things. And then once it finally works, you are afraid to touch it because it is so fragile. 9 Thats why i made sure to have the acceptance test. So that i can safely refactor it into a proper domain model. So lets do that next.

A real domain model

Refactor towards a model with behaviour

Now of course that is all fine and dandy but to Quote Linus: “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” So lets refactor the original code from Paper boy anemic domain example. Since the code is of course covered by tests this is something i’m not afraid to do. Without tests i never would attempt to rewrite an anemic domain model. It would be a nullpointer slugfest. In order to refactor the anemic domain model i took the following steps:

- removed the setters of all model objects.

- removed the getters were they were not required, not exposing anything mutable

- move the logic inside the objects.

Here you can find the complete code base for the example. It contains two branches. master contains the anemic domain model, real-model contains the refactorred model.

Advantages of a real model

The advantages of this refactoring to a real domain model with behaviour are

- The removal of the PaperBoyRoundService and the LoadPaperService. The logic now resides where it belongs. Inside the domain objects.

- The invariants are now enforced. The invariants are now properly enclosed in the domain objects. It is no longer possible to

- obtain a paper from the paperboy without paying for it

- to take al the money from the customer

- to take more money then present in a wallet.

- The domain object can be tested in isolation

Since these invariants/ business rules are now enforced it is easy to now write unit tests for the Customer, PaperBoy and Wallet. Of course we could have had unit test before before but since there was no behaviour it was rather pointless. Why would you want to test getters and setters?

The code of the real domain model

Below you can find the code of the real domain model that now enforces the invariants

The customer

public class Customer {

private final Wallet wallet;

private final Address address;

private Paper paper;

Customer(Address address, Wallet wallet) {

checkNotNull(address);

checkNotNull(wallet);

this.address = address;

this.wallet = wallet;

}

public void buyPaper(PaperBoy paperBoy) {

final MonetaryAmount price = paperBoy.getPaperPrice();

if (wantsPaper(price)) {

final MonetaryAmount money = wallet.takeMoney(price.getNumber());

final Optional<Paper> paper = paperBoy.sellPaper(money);

if (paper.isPresent())

this.setPaper(paper.get());

else

wallet.add(money);

}

}

public boolean livesHere(Address address) {

return this.address.equals(address);

}

public boolean hasMoney(MonetaryAmount customerMoney) {

return wallet.containsAmount(customerMoney);

}

public boolean hasPaper() {

return paper != null;

}

public MonetaryAmount getAmountOfMoney() {

return wallet.getAmountOfMoney();

}

public Address getAddress() {

return address;

}

private void setPaper(Paper x) {

this.paper = x;

}

private boolean wantsPaper(MonetaryAmount price) {

return !hasPaper() && hasMoney(price);

}

}The paperboy

public class PaperBoy {

private final Logger LOGGER = Logger.getLogger(this.toString());

private final Wallet wallet;

private final Stack<Paper> papers;

public PaperBoy(Wallet wallet) {

this.wallet = wallet;

this.papers = new Stack<>();

}

public void loadPapers(List<Paper> papers) {

this.papers.addAll(papers);

}

public Optional<Paper> sellPaper(MonetaryAmount money) {

if (hasSufficientMoney(money) && stillHasPapersToSell())

return makeTransfer(money);

else

return Optional.empty();

}

public MonetaryAmount getPaperPrice() {

if (papers.isEmpty())

throw new RuntimeException(this + " is out of papers!");

else

return papers.peek().getUnitPriceOfPaper();

}

public MonetaryAmount getAmountOfMoney() {

return wallet.getAmountOfMoney();

}

public int getNrOfPapers() {

return papers.size();

}

private boolean stillHasPapersToSell() {

return !papers.isEmpty();

}

private Optional<Paper> makeTransfer(MonetaryAmount money) {

wallet.add(money);

return Optional.of(papers.pop());

}

private boolean hasSufficientMoney(MonetaryAmount money) {

final MonetaryAmount priceOfPaper = getPaperPrice();

if (priceOfPaper.isGreaterThan(money)) {

logInsufficientFunds(money, priceOfPaper);

return false;

}

if (priceOfPaper.isLessThan(money))

logThxForTheTip(money, priceOfPaper);

return true;

}

private void logThxForTheTip(MonetaryAmount money, MonetaryAmount priceOfPaper) {

LOGGER.info("Thanks for the tip ! The price of the paper is " + priceOfPaper + " and gratefully received " + money);

}

private void logInsufficientFunds(MonetaryAmount money, MonetaryAmount priceOfPaper) {

LOGGER.warning("Not enough money. The price of the paper is " + priceOfPaper + " but received only " + money);

}

}The wallet

public class Wallet {

private MonetaryAmount money;

Wallet(Number amount, CurrencyUnit currency) {

this.money = of(amount, currency);

}

public Optional<MonetaryAmount> takeMoney(NumberValue amount) {

final Money extractedMoney = of(amount, money.getCurrency());

if (money.isGreaterThanOrEqualTo(extractedMoney)) {

this.money = money.subtract(extractedMoney);

return Optional.of(extractedMoney);

} else

return Optional.empty();

}

public boolean containsAmount(MonetaryAmount customerMoney) {

return money.isGreaterThanOrEqualTo(customerMoney);

}

public void add(MonetaryAmount toAdd) {

if (toAdd.isPositive())

this.money = this.money.add(toAdd);

}

public MonetaryAmount getAmountOfMoney() {

return Money.from(money);

}

}The domain model unit tests

Below you can find an simplified version of the unit tests for the real domain model. In the anemic domain model these were simply not present since there was no logic to be tested. In the real model there is real behaviour to be tested.

The Customer unit test

public class CustomerTest {

//...

@Test

public void buyPaper() {

//...

}

@Test

public void canNotBuyOverpricedPaper() {

//...

}

@Test(expected = RuntimeException.class)

public void buyPaperFromPaperLessPaperBoy() {

//...

}

@Test

public void evilPaperBoy() {

//...

}

}The Paperboy unit test

public class PaperBoyTest {

//...

@Test

public void sellPaper() {

//...

}

@Test

public void canNotSellBelowPrice() {

//...

}

@Test

public void canSellAbovePrice() {

//...

}

}The Wallet unit test

public class WalletTest {

//...

@Test

public void takeAllTheMoney() {

//...

}

@Test

public void takeHalfTheMoney() {

//...

}

@Test

public void takeToMuchMoney() {

//...

}

@Test

public void addMoney() {

//...

}

@Test

public void addNegativeMoney() {

//...

}

}Conclusion

After this long explanation of the anemic domain model i hopefully have convinced you that it is not something you should strive for in an object oriented language. It really deserves the acronym POOP 10. Where a proper Object Oriented implementation offers so much more…

References